During WWII the Russians didn’t need help with tanks – they had arguably the best all-purpose tank of the war in the T-34. Cannons? When Berlin was surrounded in 1945, it is estimated that the Soviets had close to 10,000 guns aimed at just that one city. Planes? The Russians had decent fighters by wars’ end. The Americans even gave them P-39 Airacobras, but that was because American pilots hated them.

What the Soviets lacked was a strategic bomber force. They saw first hand the damage done to German cities by the air forces of Britain and the United States and realized that they were far behind in the development of modern heavy bombers. By 1944, the best bomber on the face of the planet was not flying over Germany, however. It was raining destruction on Japanese conquests and the Japanese home islands on the other side of the world. This was the famous Boeing B-29 Superfortress.

Until the Soviet Union declared war on Japan in the closing days of August, 1945 it maintained a state of neutrality towards combatants in that theater. During this period of neutrality, allied aircraft that diverted to the Soviet Union due to weather, mechanical or battle damage issues, were impounded and their crews eventually returned to their nations of origin, though not without attempted interrogation along the way. This practice began with the Doolittle B-25s that landed in Vladivostok in 1942 and in 1944, included three B-29’s:

- On July 29, 1944 Ramp Tramp, a B-29-5-BW serial number 42-6256 that was unable to return to its base after a raid in Manchuria (landed in Vladivostok);

- On November 11, 1944 The General H.H. Arnold Special, serial number 42-6365, that was damaged during a raid against Omura on Kyushu was forced to divert to Vladivostok and;

- On November 21, 1944 Ding How, serial number 42-6358, which also landed in Vladivostok.

Stalin was continually pressured for the release of the crews and planes, however it soon became obvious that he had no intentions of giving them up. He figured it would take over five years to design and build their own much needed long range bomber.

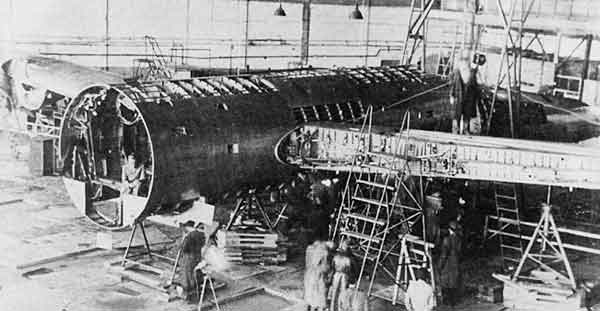

A better way would be to take these already in his possession and make a bolt for bolt exact copy of them. Stalin demanded the reproductions be ready in two years. The entire Soviet aircraft industry was mobilized to meet this seemingly impossible deadline. At that time any dissention was met with punishment, even death. That would be considered sabotage to question a project.

This project received top priority. The crews for these aircraft were eventually returned to the US (via Tehran) in January 1945.

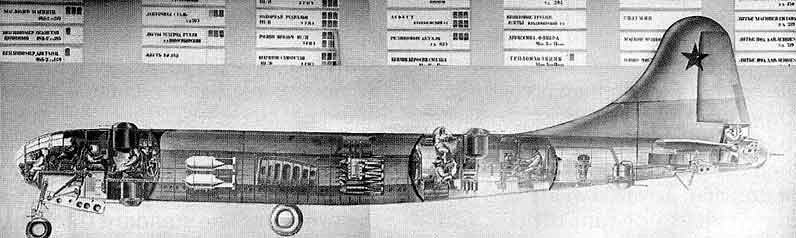

A.N. Tupelov eventually took charge of the replication process and immediately confronted the enormous challenge that they faced. The B-29 represented the ultimate of technological refinement in the US aircraft industry – using lightweight metallic alloys (including magnesium alloys) and the latest in electronic capabilities for self defense and all weather bombing, the B-29 was a veritable lodestone of information – if it could be decoded.

Under normal circumstances, this would be a many year effort, but with Stalin’s interest and imperative, the project assumed the urgency of America’s Manhattan Project, except with Stalin’s well known propensity to brutally punish failure.

To that end, when he demanded an exact copy, as close as was possible, an exact duplicate was generated. How exact? Here is one story (as related by Victor Suvarev (pen name for a critical post-war writer who had extensive experience with this effort):

“A little hole was found on the left wing of the [first] aircraft. No aerodynamics or durability expert had the slightest idead what the hell it was there for. There was no tube or wire attached to it, and there was no equivalent to it on the right wing. The opinion of a commission of experts was that the hole had been bored by a factory drill at the same time as the other holes for the rivets. So what to do? Most probably, the hole had been drilled by mistake, and later no one had bothered to fill it in as it was much too small. The chief designer was aked his opinion. ‘Do the Amercans have it?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘So why the hell are you asking me? Weren’t we ordered to make them identical! Alike as two peas?’ So, for that reason, a very small hole indeed, made with the thinnest possible drill, appeared on the left wing of all Tu-4 strategic bombers…’”

and a better known variant regarding interior paint:

“The scroll tunnel connecting cockpit and rear parts of the bomber was half green and half white, because Boeing run out of one of the color when painting this particular specimen. On the copied aircraft, two thirds was painted chromate green, the aft portion left in white primer. ‘Later, this ratio was included in all the instruction books on how to paint the interior of the bomber’.”

Finally, this measure of the paranoia present in Stalinist Russia :

“‘What kind of stars should be put on the mass-produced aircraft – white American stars of red Soviet ones? If you put white stars, you risked being shot as an enemy of the people. If you put red, first, it will not be a copy, and second maybe Stalin is planning to use the bombers against America, England or China, and therefore keep the American markings.’ The question went all the way up to Stalin himself: Beria (NKVD chief, in charge of B-29 duplication project) ‘told Stalin about the stars as if it were a funny story and that by the way in which Stalin laughed at the joke, Beria knew unerringly which stars should be used. The last problem was solved and mass-production started…’”

To perform the replication, everything, right down to bolts and fasteners, had to be converted from English to metric units. Some immediate problems were addressed, the chief one being the thickness of the aluminum skin. The B-29’s was 1/16th inch which required an impractical 1.5875 millimeter thickness in order to be an exact duplicate, therefore a skin of varying thickness between .8 and 1.8 millimeters was used instead.

However, as closely as everything else was copied, the bugs were copied as well, to include problems with the engines and props that US crews experienced (including an unfortuante tendancy to catch fire and for the electric prop governor to runaway) and other probelms with the landing gear.

Crews complained about visibility and distortion problems from the extensive glazing in the nose and the centralized self defense system also proved especially problematic. The Russians tried endlessly on solving these problems, and it was not until 1949 that the TU-4 became fully operational with some 300 in service.

0ver 900 factories and research bureaus were part of the effort to clone the B-29, all coordinated with a radio-linked production tracking process instittued by Tupelov.

The TU-4 never saw combat. Some 850 were eventually produced. Before the 60’s arrived the TU-4 had been replaced by jet aircraft. A few were given to China, and there are reports these were kept flying as late as 1968. The Ramp Tramp and the Ding Hao were scrapped. The Hap Arnold Special was never put back together. As far as we know the only remaining TU-4 is displayed at the Monino Air Force Museum outside Moscow.

Like the Stratocruiser in the US, the TU-4 was also converted to a 70 passenger airliner. The impact of the TU-4 went far beyond its actual capabilties, forcing the USAF into development of a wide-ranging early warning and interceptor system.

References:

Monino, Russia Air Force Museum: http://www.moninoaviation.com/39a.html

Soviet Military Aircraft Design and Procurement, 2nd edition. General Dynamics (Ft Worth division), 1983.